This archived website ‘James Ensor. An online museum.’ is temporarily not being updated. Certain functionality (e.g. specific searches in the collection) may no longer be available. News updates about James Ensor will appear on vlaamsekunstcollectie.be. Questions about this website? Please contact us at info@vlaamsekunstcollectie.be.

James Ensor between avant-garde and tradition

Ma meilleure joie? Ne serait-ce pas celle de constater qu'on s'est remis � peindre de vrais femmes au lieu des monstres cubiques? (James Ensor in Wyseur 1935)

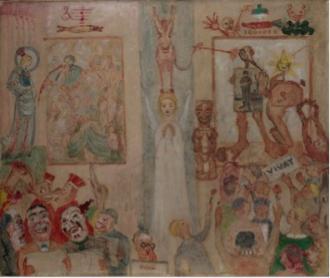

Ensor and his oeuvre were the essence of his artistry. This culminates from the 1930's in an unabashed ode to himself, his art and his ideals. There are examples aplenty: L'atelier de James Ensor (1930, Tr. 602), Nature Morte au chou rouge et � l'assiette (1930, Tr. 603), Nature Morte avec autoportrait au chapeau fleuri (ca. 1930, Tr. 604), Fleurs, fruits et masques (1931, Tr. 612), Ensor � l'harmonium (1932, Tr. 620), Ensor et les masques (1935, Tr. 655) (image 1). (2) Confrontation holds a special place within Ensor's oeuvre due to an exceptional and complex strategy of images. In place of one-sided complacency, Ensor depicts a detailed, worked-out confrontation in which he shows his never-ceasing efforts for recognition.

DISCOVERY OF AN UNKNOWN ‘ENSOR'

In 2015, an unknown painting, signed ‘Ensor' appears. It is not mentioned in the catalogue of his works of the paintings (X. Tricot, 2009), yet style, lines, colours, texture and the narrative character are undoubtedly Ensoresque. The only available historical source is a photo certificate from Galerie Georges Giroux from 1953 with the mention on it reading: La Critique sur mon oeuvre.

Dating and interpretation of the work are a complex challenge. The painting contains a wealth of elements that Ensor places on the scene. A good understanding can only come about when we reconstruct the time period of the work and get into the thoughts of Ensor. We can find a key to the search for the meaning of this painting in the Ostend paper Le Carillon from 9 March 1935. Under the fixed heading Ensoriana, the reader is promised the following: Dans une prochaine chronique, je compte entretenir mes lecteurs d'une toile récente de James Ensor intitulée ‘Confrontation' et qui est d'une irrésistible drôlerie, d'ailleurs sans méchanceté et en même temps une réussite picturale. (3) The prochaine chronique spoken of confirms that the abovementioned reference refers to the canvas that is the subject of this essay. (4) In addition to a title and a dating (une toile récente, thus at the end of 1934, beginning of 1935), we also receive an explanation of content:

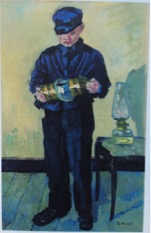

La laideur sous toutes formes lui fut de tout temps une souffrance - laideur physique, laideur morale, laideur intellectuelle - et il ne faut voir dans ses âpres satires picturales et gravées qu'une véhémente protestation d'écorché, qu'une expression de sa rancoeur sarcastique envers ceux qui salissent la vie et l'art. Tout récemment encore, James Ensor, qui ne transfigera jamais, vengeait la Beauté, trop souvent outragé depuis quinze ans dans une toile narquoise qu'il appelle ‘Confrontation'. L'on y voit, � droite, un personage baroque avec pieds énormes tenant dans ses mains ‘Le lampiste' d'Ensor (dont les pieds sont revendiqués par une certain école comme le drapeau, si l'on peut dire, de leur vison surrealiste). Au dessus de lui, une guirlande goguenarde de navets, de choux, de carottes; en dessous, des personages prudhommesques couronnant un ‘revers' triomphant. Devant ce spectacle sacrilège, Dame Peinture, au milieu se voile les yeux et pleure, tandis que, au dessus d'elle, stupide et dominant maître Aliboron (la farce énorme en fut faite avant guerre � Montmartre par quelques rapins) promené au bout de sa queu une bosse (sic) faisant office de pinceau et enfantant des chefs d'oevres fulgurants et inconnus. A gauche la vierge consolatrice tend une palme d'hommage nostalgique vers le portrait d'Ensor, entouré de figures joufflées, mafflués, rosées et flanqué du hareng saur, de la clef de sol, et des masques hilarants, qui sont ses attributs. (5)

The painting is divided up compositionally and content-wise by a central column formed by a grieving angel that bears a donkey on her head. This is the vertical axis along which two scenes play off each other with a continuous parallel build-up. On the foreground is a mass of people, masks and animals. On the middle plane are works and citations from the earlier oeuvre of Ensor. On the upper plane are the most diverse attributes such as vegetables, a herring, a musical notation and numbers. The donkey and the angel form the core of the confrontation. The angel, alias Dame Peinture, along with the left panel stand diametrically over the donkey, Maître Aliboron, the ethnic sculpture and the right-hand side. Ensor places the pure beauty and the unspoiled inspiration in contrast to, according to his opinion, the commercialised formula and the primitive ugliness.

ENSOR AVENGES BEAUTY WITH ‘DAME PEINTURE'

Tout récemment encore, James Ensor, qui ne transfigera jamais, vengeait la Beauté, trop souvent outragé depuis quinze ans dans une toile narquoise qu'il appelle 'Confrontation'. (S., 27/03/1935)

This assertion is confirmed by the discourse of the many addresses from this period in which Ensor defends beauty within various societal domains. For example, with his resistance against the building up of the Belgian coastline: Envers et contre tous au nom de la beauté, au nom de la bonté, contre le diable et son train, contre ingénieurs, architectes, ministres, petits ou grands.(6)

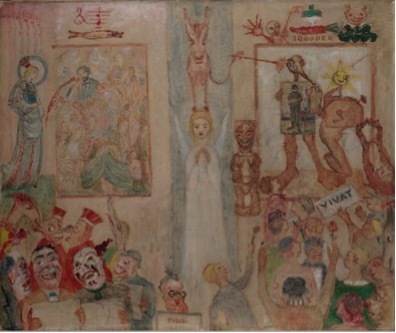

Central in the painting a static angel catches the attention. With a white garment, folded hands and tears rolling down the cheek, this is an ange pleureur (weeping angel), a classic funeral motif. Ensor depicts similar angels nearly 50 years earlier in Le Christ pleuré par les anges (image 2). While the angels in 1886 mourn for the fate of Ensor as a misunderstood, visionary artist, this angel, alias Dame Peinture, in Confrontation mourns the downfall of the pure beauty. (7)

Dame Peinture is Ensor's muse; she represents the inspiration that leads to the pure, true art of painting. Ensor grants her a sacred role and thus promotes his artistry to something metaphysical. He praises her in various essays and letters. Et crions: oui, nous serons grands, nous serons forts et sensibles...Et crions plus fort: nos femmes seront plus belles encore! Dame peinture toujours jeune, je vous donne mon coeur, je vous donne mon corps. Vive Vous! Je vous aime! (8)

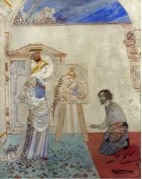

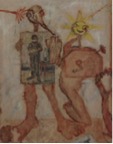

This Dame Peinture is the counterpart to the Madonna that he paints on the left. Ensor combines two paintings in an ingenious way: La Vierge Consolatrice from 1892 (Tr. 354) (image 3) and Mes Houris from 1927 (Tr. 586)(image 4). He copies the figure from the Vierge Consolatrice to which he looked up to then and before which he humbly kneeled. (9) In Confrontation she playfully moves with her lily stem the portrait of Ensor that is integrated within an adapted copy of Mes Houris. Now, Ensor is not the solitary devotee of La Vierge any more, he even becomes adored by an entourage of women. The iconography of Mes Houris is inspired by a Koran verse in which the departed is received in Paradise by youthful virgins with dark eyes called ‘houris'. (10) A noticeable detail is that Ensor depicts himself here as a 30- year old- the same age as in the work La Vierge Consolatrice- while in the original work of 1927 he appears as a white-haired and bearded 67-year old.

He paints a mix of old and new work, an exchange of early and late self-portraits. With this reinterpretation of both works, he lets it be seen that the woman is a constant in his oeuvre, already from his younger years and always still. La Vierge Consolatrice, Dame Peinture and the virgins from Mes Houris are sublimated archetypes of ‘the woman' in Ensor's universe. They represent the true beauty and bring him inspiration and comfort.

At bottom left we see a carnival group of judges, masquerades, and animal (masks?). The colourful group walks along singing, squabbling and laughing at us. Four personages are engrossed in a musical or textual sheet. The left-hand portion shows a few important themes from out his oeuvre: Beauty, the woman, crowds, song, pageants and masks. (12) The goat that comes out of the canvas on the left is the counterpart to the donkey on the other side. The goat, the symbol for the festive and Dionysian, stands here in contrast to the stupidity and stubbornness of the donkey. The physical likeness of the man with the glasses that stands bottom centre and is reading the paper on which Ensor has put his signature is strikingly like René Lyr (images 6-7). This was one of the originators of the naming of Ensor as Prince des Peintres et des Arts in 1934, to which the small crown could be indicating a noble attribute.

MASTER ALIBORON: THE DONKEY THAT THE JUDGES CONSIDER THE FOOL

In contrast to Ensor's joie de vivre and ‘profession for Beauty', the right-hand side of the canvas appears to be an inventive critique. Ensor ties a brush to the tail of the donkey and allows him to make a painting: a monstrous figure on a podium that shows a work by Ensor (Le Lampiste) next to a barrel organ.

What he allows the donkey to do is, however, not found to be so crazy. Ensor had not forgotten what enormous farce a few rascals pulled off before the war, such as his chronicler in Le Carillon writes, with the actor Maître Aliboron as central actor, a donkey! Maître Aliboron is an old nickname for the personage of the donkey. (13) With Un Maître Aliboron or un aliboron, one means a stupid, pretentious someone. (14)

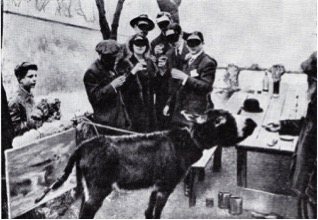

This personage and his ‘quality' were masterly manipulated by Roland Dorgelès, a young journalist and writer from Paris. In 1910 at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, he exhibited under the pseudonym Joachim-Raphaël Boronali. (15) To his delight and surprise, his painting Et le soleil s'endormit sur l'Adriatique garnered favour and was sold for the sum of 400 francs. (16) Afterwards, Dorgelès came out with the controversial revelation that this work was painted by a donkey (image 8). He had photos taken of the creative process and had everything ascertained by a bailiff. (17) Moreover, the name Boronali was a hint, namely the anagram of Aliboron. Dorgelès-Boronali likewise published a Manifesto of Excessivism in which the new trends of art such as Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism were ironically encouraged to exaggerate even more. This sensation from the cultural world of 1910 was described extensively by the press, and Maître Aliboron became a concept. By the choice of the painting donkey as the central icon, Ensor aligned himself with the vision that the pure beauty and pure inspiration were exchanged for ideas and formulas by these vulgar ‘isms'.

Ensor is a narrative artist who tells stories with his brush. The story in Confrontation runs parallel with the style and content of his previous essays. Thus the inventive language of images from the essays was translated to a complex, personal symbolism, metaphors and proverbs. The anthropomorphised barrel organ supported on one leg is a visual translation of a foot organ (image 10) and stands for the uncooperative, quarrelsome and doctrinal character of the modernist art movements. (18) Not only does he place his foot onto the canvas of Ensor, but also takes the monster ‘by the nose'. This is a literal illustration of the French saying un pied de nez: a childish gesture whereby the thumb is placed against the nose. (19) Ensor also depicts this gesture with the illustrations of a collection of Mallarmé poems and in the décor of his ballet La Gamme d'Amour (first tableau, le magasin de Grognelet, 1912) (image 9). (20) The yellow, geometric, mechanical spiky sun contrasts with Ensor's vision of light as the organic source of colour and creation. The ogre with sharp nose stands on ‘feet of clay'. A reproach that Ensor often directed at his opponents: they appear strong, but with the slightest resistance they appear very fragile and unsure, thus they can be washed away. (21)

Throughout his entire career Ensor feels passed over and misunderstood by critics and fellow artists. Thus, in 1911 he emphasises his influence on the then new generation of artist, the Cubists: [quote] (24) In 1910 he also makes a second version of Le Lampiste (image 13). In 1934-35 he revisits this thesis through Confrontation. (25) His lamplighter boy, however, now becomes part of a painting that is reproduced in the manner of that time, Surrealism. Did he want to emphasise his influence on the younger generations with both his pronouncements and his second Lampiste in 1910-11 as well as with Confrontation twenty-five years later? (26) Furthermore, did he feel misunderstood because it was not his art but the ethnic/primitive art that was taken by the new art movements as a source of inspiration? His disappointment over the lack of respect and recognition filtered through in other essays. In 1934, he uses his designation of Prince de la Peinture et de l'Art in order to express his disillusionment in the portion of the young generation that did not support him. Subsequently he launches a charm offensive to march together under the banner of beauty:

Hélas! Trois fois Hélas!!! Mes détracteurs travestis et certains jeunes d'esprit mollet, révolutionnaires � Blanc, dégraisseurs attristés de nos belles amies me sifflèrent � l'oreille: ‘'Vieux raseur, vous n'êtes pas un pur, vous écornifler les pieds des adeptes de nos créations, vous barrez nos beaux chemins courverts, vous ridiculisez les vervents de nos modes nouvelles, vous alimentez les esprits indociles'' O Ensor quand serez vous mort! Mais vous les gros mâles de 25 ans, êtes vous content? Vous me direz � la tombée des dents les cornes poussent et repoussent et pauvre baron bovin vous ruminerez bientôt la fine fleur des tisanes et le suc amer des lauriers fanés. Mais moi je vous aime, vous les jeunes artistes, vous les enfants de choeur confits, des épiciers déconfits, de profiterus inassouvis, des jouisseurs cramoisis. (...) Enfin cette fois, j'aurai raison chez vous les jeunes, ici, j'ai droit de cité parmi mes masques aimés, j'accepte avec joie le titre de Prince de la Peinture et de l'Art, parce que décerné par mes pairs, par les vrais peintres, ceux de sens, de l'esprit, des amours par ceux qui bûchent, triment, ceux qui cracheront sur leurs drapeaux la fière devise: Frères, il faut vivre. Artistes mes amis vivons, survivons, caressons les lumières vivantes de nos aimées. Célebrons la lumière, ce pain sain du peintre. (...). (27)

These exclamations help us to understand the lower-right plan: a mass of sixteen figures with the banner Vivat (Long Live), flowers and a wreath of flowers. The cheering and admiration of these young people-amongst which critics and artists?-is intended for the painting of the donkey. It is noteworthy that this group turns its back to us while the group on the left side sings to us. On the right side of the canvas a donkey's head is depicted in order to illustrate the stupidity of this mass. On the upper right, Ensor paints an enigmatic code. The infantile monster, equal to the one painted by the donkey, points to the coal and the carrot above the number 1000.000. The money on the art market is compared to the carrot for the donkey and serves as enticement and decisive authority for the masses. Here, Ensor is making an innuendo to the marketing of modern art under the influence of galleries and capitalist investors. (28) With this he shares the opinion of traditionalists as art critic Camille Mauclair that viewed L'Industrie du tableau as one of the causes for the downfall of L'Art Vivant. (29)

CONFRONTATION IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The 1930's were a decade of recession in a variety of domains. What began as an economic crisis spread out into an ideological and aesthetic crisis. An animated debate in the art world sprung up between the Fauves (Modernists) and the Pompiers (Traditionalists). The role of the artist was put into question and the Art pour l'Art idea was exchanged for a more utilitarian vision of art. (30) As much as the years were progressing, the artistic experiment was steadily more stunted to the core. Influential galleries closed their doors by necessity and the prices for Expressionist and Surrealist works crashed. The new form of expressive arts became an expression bound to reality, if not rooted in national tradition. A broader name for this movement is the Retour � l'ordre or the Retour � l'humain. (31)

The career path of Ensor spontaneously adhered to this reactionary tendency: at the end of the 19th Century, he still raised the barricades of the avant-garde, and as much as the years progressed he steadily rescinded his innovative urgency. An important aspect of his late oeuvre is the perfecting of his own aesthetic from which form, beauty, light and harmony were important pillars. Il est essentiel que l'oeuvre chante, qu'elle vibre, qu'elle bouge (...) Il faut le synchronisme parfait. L'harmonie totale, et c'est la clarté seule qui peut la procurer. (32)

Ensor took a defensive position against the avant-garde artists. The downfall of the avant-garde ran concurrently with the rising of his star. He was celebrated all over the country for his 75th birthday and his appointment as Prince de la Peinture et de l'Art. Through numerous essays, interviews and opinion pieces he received a forum in which he could vent his outspoken opinion and go after the ‘confrontation' with, among others, architects, bourgeoisie, politicians and avant-garde artists. He integrated the polarisation of the art debate at the time within the atmosphere and construct of his discourse and created a duality between friend and foe, between good and bad, and between true and false with exaggerating and baroque verbal imagery. Ensor felt in his element with respect to avant-garde artists, strengthened by influential critics such as Camille Mauclair. He asserted that there were many years lost to misfired experiments on form of a Faux Art Vivant. Il y a enfin, hélas! Les jeunes de bonne foi, ceux dont, depuis vingt ans, on a dévasté systématiquement la cervelle par le phylloxéra de l'originalité nécessaire et suffisante. (...) (33)

Ensor repeats this sharp viewpoint in an interview: Ah ce qu'on en a fait de la cochonnaille depuis trente ans! J'espère vivre assez vieux pour assister � la suprême crevaison de ceux qui ont cherché � fossoyer la lumière, les formes et la beauté. (34) He seems to want to make use of the historical context in order to put himself and his earlier oeuvre in the spotlight again. He strikes out first at-in his eyes-a failed generation of young artists; then he moves on, just as he treads on the path of light and beauty.

ILLUMINATION OF THE PAINTING

In 2015, this painting was subjugated to an extensive, documented material-technical study. (35) The x-rays, ultraviolent recordings and infrared reflectography tell a lot about the creative process. The right side with a monster, a barrel organ and an early work by Ensor (Le Lampiste) was an ensemble difficult to determine. We notice from the technical analysis that the overpaintings and changes were the most numerous on this spot of the canvas. Thus, from the radioscopy it appears that the monster was originally a personage with a hat on, possibly the ‘lamplighter boy' himself (image 12). (36) Ensor later painted over this to the present-day painting.

The many brush strokes in the underdrawing are rather hazy, unstructured and of course are worth noting. The underdrawing, down in blue pencil or chalk is often not followed, and in the right side the many blue erasures-conscious or unconsciously-are still visible through the paint. The fact that he also made additions on top of the layer of paint indicates that the work was subject to changes to the last minute.This is not a definitive hand but a searching process for the optimal depiction of a specific feeling via well-intended motives.

The various styles that he uses in the left and right panels also contribute to the content's meaning. La Vierge Consolatrice is wonderfully stylised and decorated in detail rendered in a Neo-Gothic, symbolist idiom, while the right panel, ‘the work of the donkey' is consciously rougher and superficially executed. This seems like an Ensoresque interpretation of form of Modernism. Still a few significant changes are brought to light: in the lower-right corner, the two heads were originally a kissing couple (image 14), a motif that frequently shows up in his oeuvre (image 15). The head of the men who throws his arms in the air was originally depicted frontally, with a visible face.

CONCLUSION

During the 1930's there is a polemic in the art world between innovating and stabilising. Ensor, 75 years old in the meantime, shares the idea of a Retour � l'humain and uses his status to defend this message with verve. He couples his rather conservative bent towards beauty in painting, architecture, literature and music with the social debate.

Between 1925 and 1935 he experiences a period of rising recognition. In 1929 he receives a large retrospective in the new Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels and receives the title of Baron. Later he is proclaimed the Prince de la Peinture et de l'Art by his fellow artists and for his 75th birthday, in 1935, manyfestivities are organised, as well as the unveiling of a portrait bust. And yet he felt the compulsion to paint Confrontation.

It is a painting with a layered content. It is a manifest, nearly a pamphlet, in which he defends his vision of classical beauty at the expense of the contemporary movements. The chosen images adhere to his theoretical reflections. Numerous introductions and essays overlap with this painting. He paints his vision in a polarising manner, hence the title Confrontation: the lily leaf of La Vierge Consolatrice brings inspiration, the brush of Maître Aliboron deception.

Consequently, despite the recognition, he can still not tolerate criticism of his work and subsequently himself. The wounded and hurt James lives on forever. From this comes the alternative title: La critique sur mon oeuvre. (37) He not only paints an intellectual argument but it is his emotion that colours the whole. The effort that he makes to paint ugly and unruly in the right side is compelling. It is exemplary that when Claude Spaak gives a slight jab in 1934 in an article (Ensor Vous avez trahi), immediately a direct answer (probably by Ensor himself) is organised (Ensor a-t-il trahi?), that is signed by a number of fellow artists and prominent people from the cultural world. (38)

Finally, this painting shows how Ensor applies all means in order to defend his rather unnuanced and categorical standpoint. Previously he used caricature, irony and masks as biting commentary on society. Now, laureled and praised, he uses the same means as biting commentary to the new art movements. Also in his speeches and letters he plays with rhetorical exagerations and this frequently for increasing honour and glory for himself. This painting is an illustration of his manipulative capacities. He is convinced of it and feels himself compelled as well to show that he is the forerunner of many modern ‘isms'.

By depicting early works he repositions himself in the history of art, he prolongs his place of honour and tolerates no doubts. This is the how and the why that he feeds his myth.

JAMES ENSOR'S AFTERWORD

Ma meilleure joie? Ne serait-ce pas celle de constater qu'on s'est remis � peindre de vrais femmes au lieu des monstres cubiques et tavelés qu'on nous servait jusqu'� nausea. Parlez-nous des vrais croupes, des veritables hanches, des chaudes carnations, des anatomies fondants, nacrées, irisées, arc-en-ciellisées, que les artistes se reprennent � aimer.(...) Nous revenons aux saines traditions d'art, aux visions paradisiaques, et cela nous change rafraîchissantement des anatomies angulaires et des couleurs émétiques. (...) Ah ce qu'on en a fait de la cochonnaille depuis trente ans! J'espère vivre assez vieux pour assister � la suprême crevaison de ceux qui ont cherché � fossoyer la lumière, les formes et la beauté. (39)

Footnotes

(1) It would be surprising that Ensor, who loved his art more than anything and consequently loved most of the man who made the art, namely himself, would not have multiplied his own image to infinity. (...)

(2) This listing is not exhaustive.

(3) In a forthcoming feature, I call up to entertain my readers with a recent canvas by James Ensor entitled, ‘Confrontation'. A canvas with an irresistible humour, without falling into vulgarity, and at the same time a sharp, painterly presentation.

(4) Prochaine chronique, 27/03/1935.

(5) Ugliness in all its forms means for him a torment since the beginning-physical ugliness, moral ugliness, intellectual ugliness-and one can recognise nothing other than a staunch protest in his biting painted and engraved satires, and then an expression of his sarcastic rancour against those who befoul life and art. Recently still Ensor, who shall never change, avenges Beauty, too often mocked the last 15 years, in a mischievous canvas that he calls ‘Confrontation'. We see on the right side a Baroque personage with enormous feet and Ensor's ‘Le Lampiste' in his hands (from which the feet and the curtain are claimed by a certain school, because of their, as we might say, Surrealist appearance). Above him, an absurd garland of turnips, sprouts and carrots and under him ‘Prudhommesque' figures that crown a triumphant personage. For this painting of sacrilege Dame Peinture, in the middle, closes her eyes and weeps, while above her, foolish and dominant Maître Aliboron, with a knot at the end of his tail serving as a paintbrush, unknowingly, lightning-fast produces masterpieces. (This enormous farce was carried out before the War by a few rascals in Montmartre). On the left side we see the mourning virgin who points a nostalgic palm branch towards the portrait of Ensor, ring by soft, rose figures and flanked by his attributes: a sour herring, a treble clef and pleasant masks. (S, 27/03/1935).

(6) Against the whole world in the name of beauty, in the name of goodness, against the Devil and his train, against engineers, architects, ministers great or small. (J. Ensor, 1934 in Ensor 1974:188).

(7) In 1931, Ensor wrote again on ‘Madame Couleur' in the article ‘Ostende et ses Couleurs', Yes Madame Couleur is the real painter's friend. She explains my evolution and mychanges as artist. One can say that Ensor changes his style like as it was a shirt(J. Ensor, 1931)

(8) And let us call out: yes, we shall be great, we shall be strong and emotional...And let us call out harder: our women will be yet more beautiful! Dame Peinture forever young, I give you my heart, I give you my body. Long Live! I love you. (J. Ensor, 1934 in Ensor 1974:209)

(9) That Ensor gives the figure of La Vierge Consolatrice a prominent place within Confrontation is not by chance. On 4/11/1934 he writes an article ‘Sur les vierges consolatrices' in honour of the exhibition ‘Les maîtres de la femme' in Le Studio at Ostend. He says about this work: Je la garde jalousement, elle est le mienne et je l'aime.

(10) Koran, sura 56 verses 12-40; sura 55 verses 54-56; sura 76 verses 12-22.

(11) The motif of the herring-‘hareng saur'-is also used in La Vierge consolatrice (1892).

(12) We recognise various motifs from earlier works, amongst which ‘singing masks' (i.e. Les Chanteurs grotesques; (1891, Tr.336) and Ensor et les Masques (1935, Tr. 655)) and judges (Les bons juges; 1891). The reptile and the singing masks were nearly identically recalled in Ensor et les masques (1935) (see image 1), a work that was painted in the same period as Confrontation.

(13) The nickname ‘Maître Aliboron' begins in the 14th Century and is popularised by the fable of La Fontaine ‘The donkey and the robbers' (Fables I, 13).

(14) www.cnrtl.fr/lexicographie

(15) GROJNOWSKI D. (1991), p. 41.

(16) GROJNOWSKI D. (1991), p. 46.

(17) The report of the bailiff was published in the paper Fantasio from 1/04/1910 and L'illustration from 2/04/1910.

(18) Ensor knew this instrument well, one of the pieces of his ballet La Gamme d'Amour is called‘orgue de barbarie' or barrel organ.

(19) Ensor mentions this expression many times in interviews and essays.

(20) FLORIZOONE P. (1998), p. 75.

(21) He uses the expression ‘standing of feet of clay' in the essay ‘discours adressé aux conferères masques': bâtisseurs enchevêtreés aux pieds d'argile (...) (J. Ensor, 1974:180) and in the essay Sur la crise de la peinture: Architectes aux pieds d'argile votre règne touché � la fin (J. Ensor, 1974, p. 160).

(22) Ensor probably depicts a Songye image in the Belande style here. These are recognisable by the large, laughing mouth.

(23) I condemn irrevocably the unwelcome mask that comes from the hell of Africa, Asia, Oceania, Mascacria, Dreamland and Krakozia. Naturally I transfigure with pleasure the masks that are spewed out by our infinite sea. (...) Mouth shut, enchanting magicians, all too believed Congolising idol worshippers, plundered followers on black seed. And away and away! (...)

(24) A consolation! Indeed, the Cubist mention the angles of Le Lampiste (1888) and the lines of Le Liseur (1881) as important precedents, variations of beauty (...) (J. Ensor, 1911 in Ensor 1974:13-20).

(25) In Confrontation it is the second version of Le Lampiste that he copies. The blue colour and form of the glass from the lamp confirms that, and the format of the second version is ‘more tolerable'. Yet, he has here also added the date '80, which only exists on the first version.

(26) During his career, Ensor continued to relativise Modernism and at the same time cultivates his role as pioneer with necessary irony. In 1925 he says about his early works: Quand je refeuillette mes cartons de 1877, je retrouve des angles cubists, des éclats futurists, des flocons impressionists, des chevaliers dada, des attaches constructives [sic]. (J. Ensor, 1925 in Ensor 1974:95).

(27) Alas, three times alas!!! My muted attackers and some mindweak youths, easy agressive revolutionaries, known degreasers of our beautiful girlfriends, whisper to me in the ear: ‘Old sour puss, you are no pure one, you step on the toes of the disciples of our creations, you barricade our nicely covered paths, you make the fans of our new fashion ridiculous, you feed the obstinate spirits. O Ensor, when shall you die! But, you, fat little men of twenty-five, are you satisfied? You shall say to me: when the teeth fall out, the horns grow and they grow again and, poor cattle baron, you shall soon chew the best herbal drinks and the bitter sap of withered laurels. But I love you, young artists, choirboys of art, I want to say to the old sugar-sweet peas, of the mourning herbalists, of the unsatisfied wishmakers, of the scarlet decadents (...). Ah come, this time I shall be right with you, youths, here I have freedom under my beloved masks, I joyfully accept the title of Prince of Painting and Art because this was bestowed by my peers, by the true painters, those of the senses, of the spirit, of love, painters who train, toil and those who shall span proud slogans on their banners: ‘Brothers, we must live'. Artist friends, let us live, survive, the living light of our loves caressing. We bring honour to the light, the healthy nourishment of the painter (...). (J. Ensor, 1934 in Ensor 1974:182-183)

(28) Here he shares the opinion of traditionalists such as art critic Camille Mauclair viewd the L'Industrie du tableau as one of the causes for the fall of L'Art Vivant. I only fight le faux nouveau', the false originality and the absurd. And I reverse to the fake artists launched by a consortium of merchands and brokers. (C. Mauclair 1929 in Bernard 1929:20).

(29) This assertion, however, is far from the truth. Charles Bernard refutes these statements already in 1929 in Les pompiers en délire by asserting that the majority of the Brussels galleries sold median-priced figurative art for which Mauclair fights. A few years later, during the crisis of the 1930's, it is also the modern art movements that shall be hardest hit.

(30) DEVILLEZ V. (2003), p. 15.

(31) HENNEMAN I (1992), p. 152.

(32) It is essential that the work sings, that it vibrates, that it moves (...) one must strive towards the perfect accordance. The perfect harmony, and it is only through clarity that one can reach that. (J. Ensor, 1935 in Wyseur, 1935)

(33) There are ultimately, alas!, the well-believing youths, of whom during twenty years the brains are systematically mismanaged by the laziness of the necessary and presumptuous originality. (C. Mauclair, 1929:17)

(34) Ach, what filth have some produced the last thirty years. I hope to live long enough the view the ultimate demise of those who have tried to bury the light, the form and beauty. (J. Ensor, 1935 in Wyseur, 1935)

(35) BRAKEBUSCH B. (2015).

(36) Le Lampiste and La Vierge Consolatrice could form counterparts of each other as personages from two of Ensors most praised works.

(37) On the certificate that was drawn up at the sale of purchase of the work in 1953 at Galerie G. Giroux states that La critique sur mon oeuvre is mentioned as the title.

(38) These articles appear respectively in Plan (1/04/1934) and Le Rouge et le noir (18/04/1934).

(39) My greatest joy? That can be none other than the assertion that one paints real women again instead of Cubist and blotted monsters that one offers us until one becomes nauseous. Let us speak about real crosses, truthful angles, warm carnations, fondant anatomies, pearls, irises, rainbows, which the artists begin to love again. (...) We return to the healthy tradition of art, to the heavenly visions and that as a refreshing exchange for the angular bodies and nauseating colours (...) Ach, what filth have some produced in the last thirty years. I hope to live long enough the view the ultimate demise of those who have tried to bury the light, the form and beauty. (J. Ensor, 1935 in Wyseur, 1935)

Patrick Florizoone en Willem Coppejans