This archived website ‘James Ensor. An online museum.’ is temporarily not being updated. Certain functionality (e.g. specific searches in the collection) may no longer be available. News updates about James Ensor will appear on vlaamsekunstcollectie.be. Questions about this website? Please contact us at info@vlaamsekunstcollectie.be.

'La Tentation de saint Antoine (The Temptation of St Anthony)' by Gustave Flaubert, read and interpreted by James Ensor

by Xavier Tricot

Starting in the early 1880s, James Ensor is in contact with the couple Ernest and Mariette Rousseau from Brussels, with whom he became acquainted thanks to the Brussels writer and painter Théo Hannon (1851-1916). Ensor met Hannon while he was still studying at the Brussels Royal Academy for Fine Arts. Théo Hannon was the brother of Mariette Rousseau (1850-1926), the wife of Ernest Rousseau (1831-1908), who was professor and president at the Université Libre de Bruxelles.(1)

Beginning in 1883, Ensor regularly sent them letters, postcards and drawings and was frequently a guest of theirs. This correspondence, consisting of more than 400 letters, shall cover a period of time lasting more than thirty years. This treasure trove of data is essential for a proper understanding of the complex personality of the artist and of his multi-faceted oeuvre.(2) The letters comprise, as it were, a journal of sorts that he never kept. As such, in his first letters, Ensor initially appears uncertain with regards to his spelling and writing style. In order to accomplish himself in writing, he copies texts by French authors. It is clear that he not only desires to gain perfect control over his paintbrush, but just as much so over his writing pen. On 31 March 1884, Ensor writes to Mariette Rousseau:

Maintenant j'écris beaucoup. Je voudrais acquérir ce qu'on appelle [le] Style. Je copie des lettres de Flaubert � G. Sand.(3) Je trouve son style très bref. Il ne met presque jamais de virgule. Malgré ça il est très profond et se fait bien comprendre (par moi). Quand j'écrirai convenablement vous verrez souvent de mon écriture. Je n'aurai plus inquiétude de voir Madame Rousseau découvrir quelque énorme faute (accent circonflexe manquant, i sans point). Je dormirai tranquille.(4)

In time, a proper friendship develops between James Ensor and his sister Marie (Mitche) on the one hand, and Mariette Rousseau and her son Ernest Rousseau, Jr. on the other. Already from the earliest letters it is patently clear that Ensor has found a sounding board in the person of Mariette Rousseau. She ultimately becomes his support and sanctuary. On 9 January 1887, he writes to Mariette Rousseau after he had received a book about the French artist Jacques Callot (1592-1635):

Je reçois les mitaines et le livre suprêmement interressant [sic].(5) Vous êtes aimable et aimable mille fois. Quelles diableries étourdissantes ! Callot a été influencé. C'est Jérôme Bosch qui a fait cela. Avez-vous vu � 'l'Art ancien' son tableau : un ermite tourmenté par des poissons diaboliques ? L'exécution était nulle, ni ton ni lumière ni dessin correct, mais une invention et imagination diabolique impressionnant. Vivement les gens nerveux.(6)

Ensor alludes to the work, The Temptation of St Anthony, which at the time was attributed to Jeroen Bosch, and that had just been acquired by the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (KMSKB) in Brussels.(7) Perhaps he had also, thanks to the Rousseau couple, discovered and read La Tentation de saint Antoine by the French writer Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880). After being published by Georges Charpentier (Paris) in 1874, Flaubert's "proem" was a favoured subject of painters and engravers including the French painter Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) and the Belgian artist Félicien Rops (1833-1898), whose interpretation of the legend may unquestionably be named as one of the most famous, or rather, infamous. (8)

The French artist Odilon Redon (1840-1916) was likewise inspired by Flaubert. In 1888, the Brussels publisher Edmond Deman produced La Tentation de Saint Antione, an album with lithographs, which was announced and reviewed in the 21 October 1887 edition of L'Art Moderne.(9) In 1886, Edmond Picard and Octave Mause invite Redon to participate in the annual exhibition of Les XX. He exhibits eight drawings there, amongst which are Le Masque de la Mort Rouge (after the novel by Edgar Allan Poe, The Mask of the Red Death) and three series of lithographs (Dans le Rêve, Hommage � Poë [sic] and Hommage � Goya).(10) Redon's work, incidentally, was highly regarded by only a few Belgian writers and art critics. The Brussels attorney and critic Edmond Picard (1836-1924) owned various works by the French painter, including Le Masque de la Mort Rouge (1883; MoMA, NYC) and Un Homme du peuple (1887; MSK, Ghent); and Edmond Deman (1875-1918) owned, amongst others, Tête du Christ (1878/1880; KMSKB, Brussels). Already in 1883, Fernand Khnopff had made a painting inspired by Flaubert entitled D'Après Flaubert. La Tentation de saint Antoine.(11) The following year he exhibits the work at the first salon of Les XX in Brussels.(12) In 1887, he exhibits it at the salon of L'Art indépendent in Antwerp.(13)

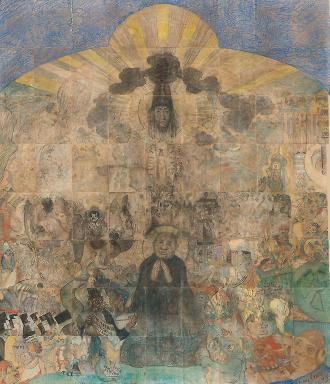

Ultimately Ensor has a go at an interpretation of The Temptation of St Anthony as well during the autumn of 1887.(14) In September or October of 1887, Ensor writes to Ernest and Mariette Rousseau:

Je travaille ferme. Et n'écris pas même pas � vous. La tentation de St Antoine me donne de la peine [...] Je suis très content de la Tentation de St Antoine. J'ai ajouté encore quelques centaines de figures : diables atroces, animaux horribles, monstres infects et indécents. Je suis très satisfait.(15)

On 28 January 1888, Ensor writes to Mariette Rousseau about how his mother's sister, Aunt Mimi, had adhered the pieces of paper onto a large sheet of paper:

La Tante Mimi colle parfaitement [les] dessins. Résultat magnifique ! La Tentation sera probablement entièrement collée pour demain.(16)

Ensor plans to exhibit the drawing at the next salon of Les XX with six other drawings and fifteen paintings.(17) According to certain witnesses, Ensor would only exhibit the drawings, amongst which is La Tentation de Saint Antoine. In an anonymous article of La Chronique of 20-21 February 1888, one reads:

Le brave impressionniste James Ensor lui-même a failli voir tout son envoi refusé en bloc. Mais comme il a montré des dents mieux acérées que celles des roquets désireux de ce jour pour lui aux cerbères devant la boutique des XX, son œuvre a été admise et � partir de demain le public pourra contempler � loisir ses eaux-fortes originales et sa prestigieuse Tentation de St-Antoine. (18)

The drawing is mentioned in the catalogue of Les XX, accompanied by a citation from Legende oder der Christliche Sternhimmel (Das Christliche Jahr. Verzeichnis der Heiligen vom 1. Januar bis 31. Dezember) by the Swiss theologian Alban Stolz (1808-1883):

Un jour qu'il venait d'être tenté plus que de coutume, il lui sembla que Notre Seigneur lui apparaissait rayonnant de lumière. Il lui dit en soupirant : « Bon Jésus, où donc avez-vous été ? Pourquoi n'êtes-vous pas venu plus tôt me secourir ? » Et il lui fut répondu : « Pendant que vous combattiez j'étais près de vous ; car sachez que je vous assisterai toujours. »

Mais le diable sans se lasser, lui tendit d'autres pièges. Il sema dans son cœur des pensées impudiques, il lui suggéra des désirs honteux : pendant son sommeil il suscita dans son imagination des rêves lubriques. (Vie des Saints par Alban Stolz, docteur en théologie et conseiller ecclésiastique).(19)

James Ensor quotes these two passages - in reverse order - from the French translation of the work by Alban Stolz, Légendes ou Vie des Saints, published in 1867.(20) In 1889 the drawing is exhibited again at the salon of Les XX.(21) Regarding the work, we read in L'Art Moderne of 24 February 1889:

Quant aux peintres, � quel fantastique puéril M. Ensor a-t-il recours ? Les monstruosités falotes et moyen-âgeuses [sic], qui peut-être effrayaient les contemporains des Bosch et des Breugel et tentaient les saint Antoine de leur temps, nous laissent indifférents - nous ne les trouvons même plus amusants.(22)

Shorn bald and without beard, with a full face and sitting as a peaceful Buddha, Anthony forms the subject of all possible mockeries and temptations that he ostensibly endures without resistance. His visions are partially those of the saintly hermit such as are described in La Tentation de Saint Antoine by Gustave Flaubert. The confounding character of the drawing is in accordance with the hallucinations described by the French writer in which Eastern temples, exotic gardens, false prophets, idols and processions of fantastic monsters follow one another in a deluge of complex images. The gigantic snake, or worm, that squirms amongst the chimeras and monsters refers to a passage from Flaubert:

C'est une tête de mort, avec une couronne de roses. Elle domine un torse de femme d'une blancheur nacrée. En dessous un linceul de points d'or fait comme une queue ; - et tout le corps ondule � la manière d'un ver gigantesque qui se tiendrait debout.(23)

To the right of Anthony's head we can discern scenes of torture that Ensor takes up again in 1899 in his sketch Queen Parysatis as well as in his drawing from 1896, Small Persian Tortures.(24) Above left, there appears to be train wreck in progress. In some satirical prints by Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) we likewise find vehicles that are traversing the sky, such as in Tableau de la ville superbe de Krrrrrtvlmfbchqdnqzw.(25) The train wreck is taken up again later by Ensor in his sketches from 1888, The Cataclysms and Devils Trashing Angels and Archangels.(26) Other scenes were more or less identically copied in his The Infernal Cortage from 1887.(27) He integrates the subject of the sketch, entitled The Flagellation, from 1886, into the composition of his drawing. He presents a church door in at the foot of which a small group of soldiers in exotic costume are eyeing four naked women. One of the women is whipping with a bundle of rods another woman who is bent over enduring the torture. This scene could be inspired by a passage from Flaubert's work:

Cependant le peuple torturait les confesseurs, et la soif du martyre m'entraîna dans Alexandrie. La persécution avait cessé depuis trois jours. Comme je m'en retournais, un flot de monde m'arrêta devant le temple de Sérapis. C'était, me dit-on, un dernier exemple que le gouverneur voulait faire. Au milieu du portique, en plein soleil, une femme nue était attachée contre une colonne, deux soldats la fouettant avec des lanières ; � chacun des coups son corps entier se tordait.(28)

If we investigate the drawing further, we discover, also to the right of the train wreck, a hot-air balloon that crashes into the void. Under the balloon, one perceives an elephant being ridden by a mahout that is holding a banner and then to the right an octopus is looming in the middle of the pandemonium. In 1888, Ensor engraves The Elephant's Joke in which a mahout is riding an elephant. This seems to depict the cataclysm of the Apocalypse in part. The void in which the world is collapsing is populated by minuscule beings such as those depicted in the scientific books and journals of the time. Just as Odilon Redon was initiated into the secret world of plants and animals by his friend Armand Clavaud (1828-1890), so too did Mariette Rousseau introduce the painter into the wonderful world of microbes, spores, amoebas and bacteria. This micro-cosmos would likewise be revealed through the media of didactic prints in popular journals such as Le Magasin pittoresque and La Science pour tous.(30) In addition to his caricature work, J.J. Grandville also made various woodcuts with scientific subjects for Le Magasin pittoresque.(31)

In the bottom left of the composition, a parade of morticians are departing of which each of them are wearing a high hat on that are provided with a inscription. The personage at the head of the procession is holding a chicken or bird of sorts in his right hand and in his left hand he is holding a plate onto which a mythical creature is relieving itself. On his sash we read: "VIVE ANTOINE NOTRE SEIGNEUR" and at his feet "ST JULIEN/ST ÉMILION". Perhaps the latter citation refers to two well-known labels of wine from the Bordeaux region. "St Julien" could likewise refer to the Légende de Saint-Julien L'Hospitalier, a work by Flaubert from 1875.(32) The personage in the foreground is carrying a skillet on his shoulder with the word "FRITES" on it and on his top hat we can read "BON BOUDINS/FRICASSÉS". The famished Anthony is dreaming of tasty food, that much is clear. On the bottom right, another grotesque personage (Athanasius, Anthony's student?) is feasting on an enormous fish. To the right of Anthony's head, a dog's head appears, drawn with a refined precision on a separate sheet of paper, in the midst of an inextricable claw. Above the dog, a strange figure is blowing a gigantic trumpet on which is to read: "Pierre, lève-toi et mange" ("Peter, rise up and eat"). Ensor copies this sentence from a passage out of Flaubert's work in which it is described how Anthony opens the book, Vie des apôtres, and reads:

Si je prenais... la Vie des apôtres ?... oui !... n'importe où ! « Il vit le ciel ouvert avec une grande nappe qui descendait par les quatre coins, dans laquelle il y avait toutes sortes d'animaux terrestres et de bêtes sauvages, de reptiles et d'oiseaux ; et une voix lui dit : Pierre, lève-toi ! tue et mange ! » (33)

The passage cited refers to the vision of St Peter. In the French-language version of the Acts of the Apostles (Actes des apôtres, 10:10-14), one reads:

Il eut faim, et il voulut manger. Pendant qu'on lui préparait � manger, il tomba en extase. Il vit le ciel ouvert, et un objet semblable � une grande nappe attachée par les quatre coins, qui descendait et s'abaissait vers la terre, et où se trouvaient tous les quadrupèdes et les reptiles de la terre et les oiseaux du ciel. Et une voix lui dit : Lève-toi, Pierre, tue et mange.

In place of the original title, Actes des apôtres, Flaubert states Vie des apôtres. Ensor takes the sentence "Pierre, lève-toi! tue et mange" quite literally from Flaubert. The citation is a bit odd appearing in a work in which Anthony and not Peter is the subject at hand. This reference shows that Ensor had undoubtedly read La Tentation de Saint Antoine by Flaubert.

On the right of the drawing, above the gargantuan head and below the parade that tumbles from above down below, we can discern a wheel from a car or artillery wagon that is drawn in green. Above the head of Anthony a naked woman appears in a shell-shaped alcove, who is most likely the queen of Saba. And, at the very top of the composition - in a solar disk - the head of Christ appears (with a strange head covering), which illuminates the cloudy sky with its rays. At the end of Flaubert's work we read:

Le jour enfin paraît ; et comme les rideaux d'un tabernacle qu'on relève, des nuages d'or en s'enroulant � larges volutes découvrent le ciel. Tout au milieu et dans le disque même du soleil, rayonne la face de Jésus-Christ.(34)

The arch that is drawn at the top of the composition, as well as the patchwork of the separate leaves, provides the whole drawing with the occurrence of a burning glass that allows the golden light to shine through. In a sort of horror vacui, images are multiplying in which Christian and profane motifs appear amongst Eastern deities, monstrous figures, anachronistic elements (trains, pushcarts,...), as well as references to painting and the common kitchen, with everything rendered in a detailed account and a dazzling sense of detail. Regarding the drawing, Karel van de Woestijne (1878-1929) wrote in 1928 the following:

Gij zijt tegen des duivels bezoeken paraat: gij moogt het heilige naderen. Wat gij heel secuur hebt aangewezen in, bijvoorbeeld, uwe teekening van Sint Antonius. "Ik heb nooit een geschilderde Antonius gezien, of van dien Antonius gelezen, die beter bestand was tegen de Sluwheid, dan de uwe. Bij zoo goed als alle plastici of literatoren is de heilige heremijt een geteisterde, die bij kastijding vechten moet: welke vergissing! Hoe hebben die al te menschelijke menschen getoond dat zij van heiligheid maar een pover begrip bezitten! Gij-zelf hebt u nooit met heiligheid gegorgeld, noch zelfs een moreele grootheid voorgegeven, die huichelarij zou zijn geweest. Zonder nederigheid, schaamt gij u niet voor humane kleinheid. Maar acuut heb gij begrepen, dat heiligheid de meest-berooide eenvoud is, de eenvoud waar men niet meer afnemen kan, en waar men zelfs geen begeert van mag verwachten. Uw heilige Antonius is een Vlaamsche boer na den arbeid, die eenigszins versuft van moeheid, maar er door verrijkt - hij ken het loon van zijn verhitte handpalmen - zijne rust geniet. Laat Phrynè om hem heen draaien en de man met de gebraden worsten; laat de lubriekste lol hem lokken of de raadselen der onbegrijpelijke perversiteit; hij blijft onaangedaan, omdat zijn leven, het feit van zijn wezen nu eenmaal een doel hebben, waar hij niet van begrijpen kan dat men ervan afwijken zou. Hij zit daar, met den slimmen deemoed van zijn oogen, als een blok graniet: hij is het graniet der onaandoenbaarheid. Binnen in hem is daar de aanhoudende wisseling der cellen, en hij gevoelt het. Maar dat is geen reactie op de werking der buiten-wereld: het is alleen het teeken van zijn bestaan, de handeling van het leven in hem, dat hem God bewijst. Wat voor hem alles is.(35)

NOTES

(1) Letters in the possession of the Rousseau Foundation (Fonds Rousseau) of the AHKB, KMSKB, Brussels.

(2) The correspondence of letters published by Peter Lang (Bern) in 2020, provided with notes and bi-lingual essay by Jean-Philippe Huys and Xavier Tricot.

(3) Lettres de Gustave Flaubert � George Sand, précédé d'une étude par Guy de Maupassant, Paris, G. Charpentier and Cie Éditeurs, 1884.

(4) Rousseau Foundation (Fonds Rousseau), AHKB, KMSKB, Brussels, inv. nr. 119.646.

(5) A publication about the French artist Jacques Callot (1592-1635), probably that of Marius Vachon, Jacques Callot, Paris, Rouam, 1886.

(6) Rousseau Foundation (Fonds Rousseau), AHKB, KMSKB, Brussels, inv. nr. 119.691.

(7) Follower of the Studio of Jeroen Bosch, The Temptation of St Anthony, ca. 1520-1530, oil on wood, 133,5 x 118 cm (middle panel), 13,5 x 52,5 cm (left panel), 130,5 x 52,5 cm (right panel), KMSKB, Brussels (inv. nr. 3032). Purchased in 1887 via mediation by Sir Julius Ruhm to Count Redern, Berlin.

(8) Félicien Rops, La Tentation de saint Antoine, 1878, pastel and pencil on paper, 737 x 544 mm, Brussels, KBR, Print Room (inv. nr. S I 23043).

(9) L'Art Moderne, 6th volume, nr. 12, 21.3.1887, pp. 339-340.

(10) Les XX. Catalogue des dix expositions annuelles, Brussels, Centre International pour l'étude du XIXe siècle, 1981, p. 63.

(11) Fernand Khnopff, D'Après Flaubert. La Tentation de saint Antoine, 1883, oil, gouache and charcoal on paper 85 x 85 cm, KMSKB, Brussels (inv. nr. GC 177).

(12) Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Les XX, 1ste salon, 2.2-2.3.1884, cat. nr. 6.

(13) Antwerp, Palais de l'Industrie, des Arts et du Commerce, L'Art Indépendant, 1ste tentoonstelling, maart-april 1887, cat. nr. 84.

(14) The Temptation of St Anthony, 1887, coloured pencil, pencil, Conté pencil, charcoal, coloured chalk, watercolour, collage on 51 sheets of paper, adhered on paper, 179,5 x 154,7 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (inv. nr. 2006.87).

(15) Rousseau Foundation (Fonds Rousseau), AHKB, KMSKB, Brussels, inv. nr. 119.701.

(16) Rousseau Foundation (Fonds Rousseau), AHKB, KMSKB, Brussels, inv. nr. 119.703.

(17) Les XX. Catalogue des dix expositions annuelles, Brussels, Centre International pour l'étude du XIXe siècle, 1981, Brussels, p. 146.

(18) La Chronique, 21st volume, nr. 50, 20-21.2.1888, p. 2.

(19) Alban Stolz, Legende oder der Christliche Sternhimmel, Freiburg, Herder, 1867.

(20) Alban Stolz, Légendes ou Vie des Saints, B. Herder, Freiburg and Brisgau & Strasbourg, 1868, p.44.

(21) Les XX. Catalogue des dix expositions annuelles, Brussels, Centre International pour l'étude du XIXe siècle, 1981, Brussels, p. 183.

(22) L'Art Moderne, vol. 9, nr. 8, 24.2.1889, p. 57.

(23) Gustave Flaubert, Oeuvres, vol. 1, Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléidade, 1951, p. 154.

(24) Taevernier 116; Elesh 121. For the drawing Small Persian Tortures, see Robert Hoozee, Sabine Bown-Taevernier, J.F. Heijbroek, James Ensor. Prints and Drawings, Mercatorfonds, Antwerp, 1987, nr. 102, p. 149.

(25) Daumier Register 5099; Bouvy 95; Rümann 38.

(26) Taevernier 37; Elesh 37. Taevernier 23; Elesh 23.

(27) Taevernier 10; Elesh 9.

(28) Flaubert, op. cit., p. 27.

(29) Taevernier 51; Elesh 9.

(30) See Le Magasin pittoresque, vol. 1, nr. 19, 1833, pp. 145-46.

(31) See Ursula Harter, "The Secret of Embryonic Life--from the Water Drop to the Micro-Ocean", exhibition cat. As in a dream. Odilon Redon, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, 2007, pp. 87-93.

(32) La Légende de Saint Julien L'Hospitalier, in Flaubert, Oeuvres, vol. II, Paris, Gallimard, Bliblithèque de la Pléiade, 1952, pp. 623-48.

(33) Gustave Flaubert, Oeuvres, vol. 1, Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1951, p. 30.

(34) Ibid., p. 164.

(35) Karel van de Woestijne, "James Ensor: Aspecten", Elsevier's Geïllustreerd Maandschrift, vol. 38, nr. 75, January-June 1928, p. 88.